Slightly Incremental Ray Tracing In One Weekend

Code for this post can be found here

Incremental Computation

Incremental computation is a programming abstraction which gives users a way of writing calculations such that, when some of the inputs change, only a relevant subset of the calculation has to be recomputed.

The above definition is kind of vague and honestly it's best to start with an example. Let's take a look at the following mathematical expression.

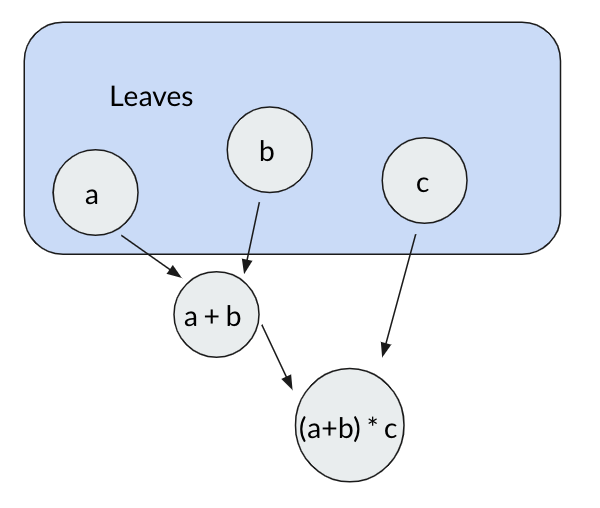

We can evaluate this expression in two steps. First by adding a and b together, and then by multiplying the result by c. We can even write this computation out as a dependency graph:

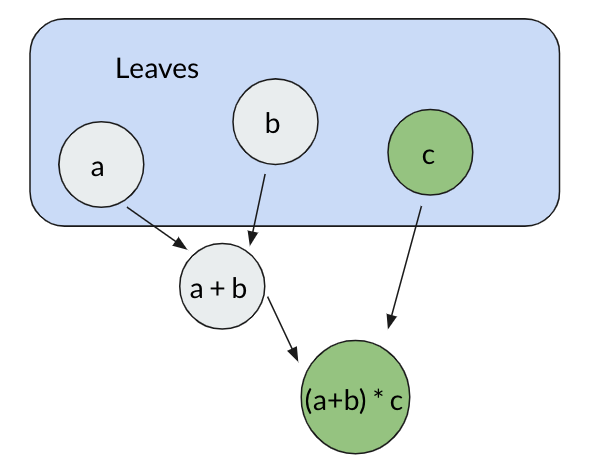

Here the variables a, b, c are referred to as leaves because they have no dependencies. Now what if after we do our initial computation, the value of c changes?

We can see from this graph that since (a+b) does not depend on c, we do not need to recompute it. Now imagine scaling this idea up to larger, more complex expressions. If you are familiar with spreadsheet software, you might have flashbacks to the huge interlinked computations created there. This brings us to a second, more intuitive definition of incremental computation: Microsoft Excel on steroids.

There are several different frameworks and projects for incremental computation. These include several rust libraries, Facebook's Skip Lang and an OCaml library called Incremental. I chose to play around with Incremental for my experiments, because it seems to be the most battle tested option.

Pros/Cons

So far it may seem like incremental computation frameworks are magical abstractions which allow programmers to write incredibly efficient programs with ease. So why don't we all use them? Well like most things in software, incremental computation frameworks come with a few trade offs.

Pros:

- An incremental computation framework provides a simple abstraction around optimizing computations which allow programmers to write more efficiently computable programs with low mental overhead.

- The abstraction provided by these frameworks generalizes well to many different types of problems.

Cons:

- The frameworks have non negligible overhead both in speed and memory. We need to make sure the computation is slow enough to justify incrementalizing. If not, the overhead of the framework could dwarf the time it would take to recompute the expression from scratch.

- Similar to the above point, the initial computation of the algorithm will be slower. You need to decide if you will be recomputing often enough to justify this slow down.

- There are always limitations to any particular abstraction. Therefore you will likely be able to come up with a custom algorithm for a specific problem that is much faster than the result you get using an incremental computation framework.

Those interested in exploring these tradeoffs in detail or wanting to peek behind the curtain will enjoy this talk.

How do people use Incremental Computation

So where are people actually using incremental computation? As far as I know, there are a few different areas where these ideas are being applied:

- Finance, especially to deal with large spreadsheet-like calculations. Most finance companies are a little vague about what they actually do, so I don't know too much about this use case.

- Compliers, the rust compiler explored these techniques when building their incremental compilation features.

- Databases, the company Materialize uses technology based on the Timely Dataflow Model developed by Microsoft Research to create a better streaming database.

- User Interfaces, user interfaces are a perfect place for incremental computation because it's important to figure out which components you actually need to re-render when something on the page changes.

How people shouldn't use Incremental Computation

Now we can get to the fun part. Over the last week, I tried to play around with Incremental (and picked up scraps of OCaml) to get a better idea of how to actually build incremental computations.

Of course the first thing I did was to break the library, but after that I decided I wanted to write a small but non trivial project which used it. Since I don't have legions of highly paid quants to create large spreadsheets, I decided that use case was off the table. I felt that building a toy compiler or database would be at least a week long project by itself without incrementalizing it, so I ruled those out as well. I'm also not a huge frontend person, so a ui framework didn't seem appeal to me that much. Instead I decided to try something different:

I decided to implement (3/4s of) Peter Shirley's Ray Tracing in One Weekend tutorial in OCaml and then try to incrementalize a part of the ray tracing step. I will be honest, this experiment was not the most amazing thing in the world, but I think I learned a lot about what not to do with incremental computation.

Is this a terrible idea? Absolutely! But we can learn a lot but understanding why exactly it's terrible.

So how does the graph based incremental computation I talked about above even fit in with ray tracing? It turns out shooting light rays into space can be thought of as a graph.

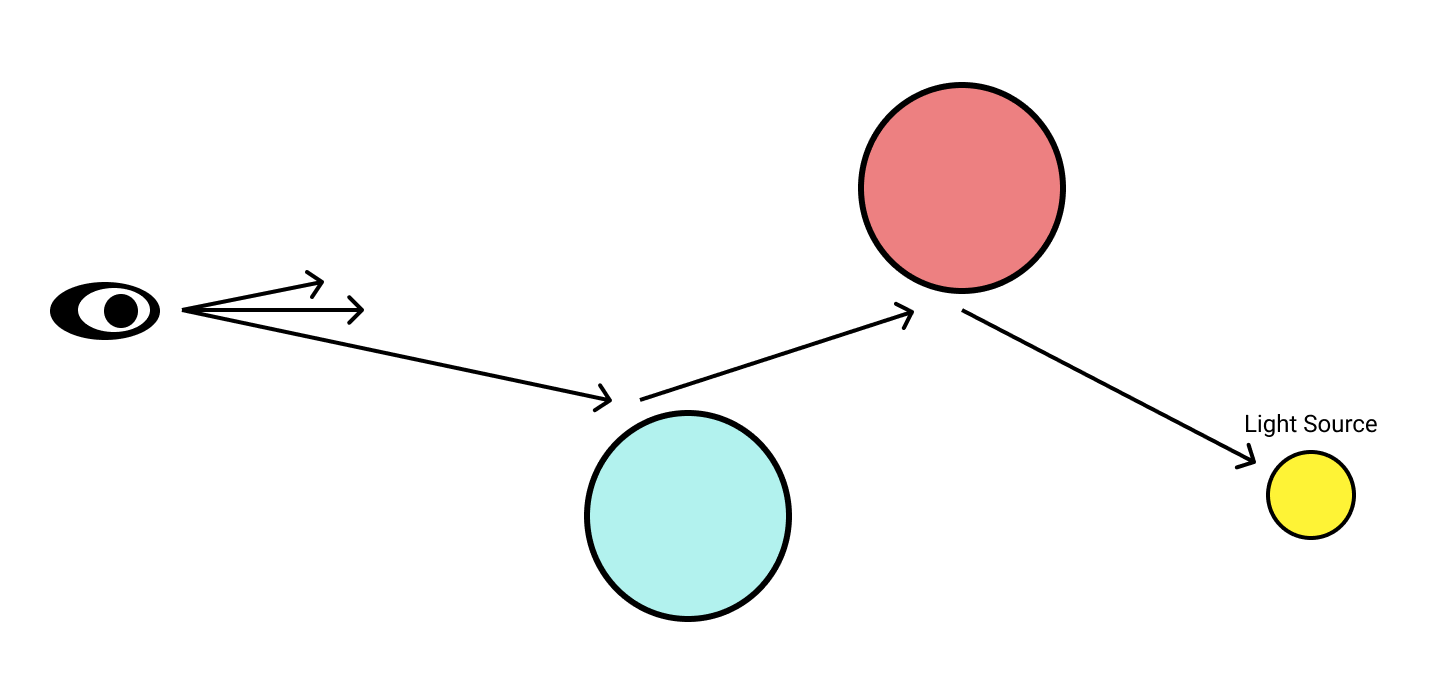

First of all let's look the process of tracing one ray of light from observer to light source.

In the above diagram, we can see a ray of light traced backwards from the viewers eye to a light source. In between, it bounces off of both a red and blue sphere.

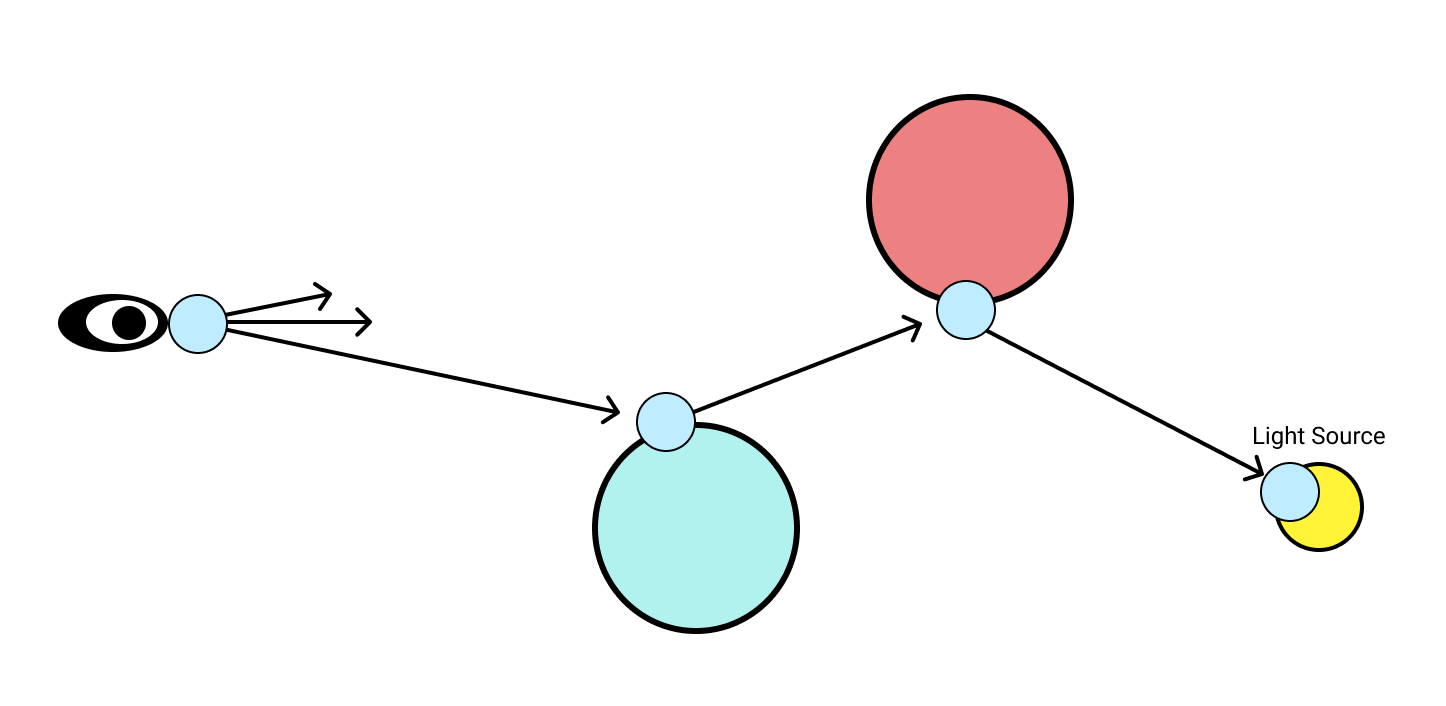

The light blue circles are nodes in an incremental computation graph and the arrows are directed edges between them. Whenever a ray hits an object, a new incremental node is created. This node computes the location of the next bounce by reflecting the incoming ray, and depends on the location and direction of the last bounce. This means that if the direction of a previous ray in the chain changes, all subsequent ray bounces will be recomputed.

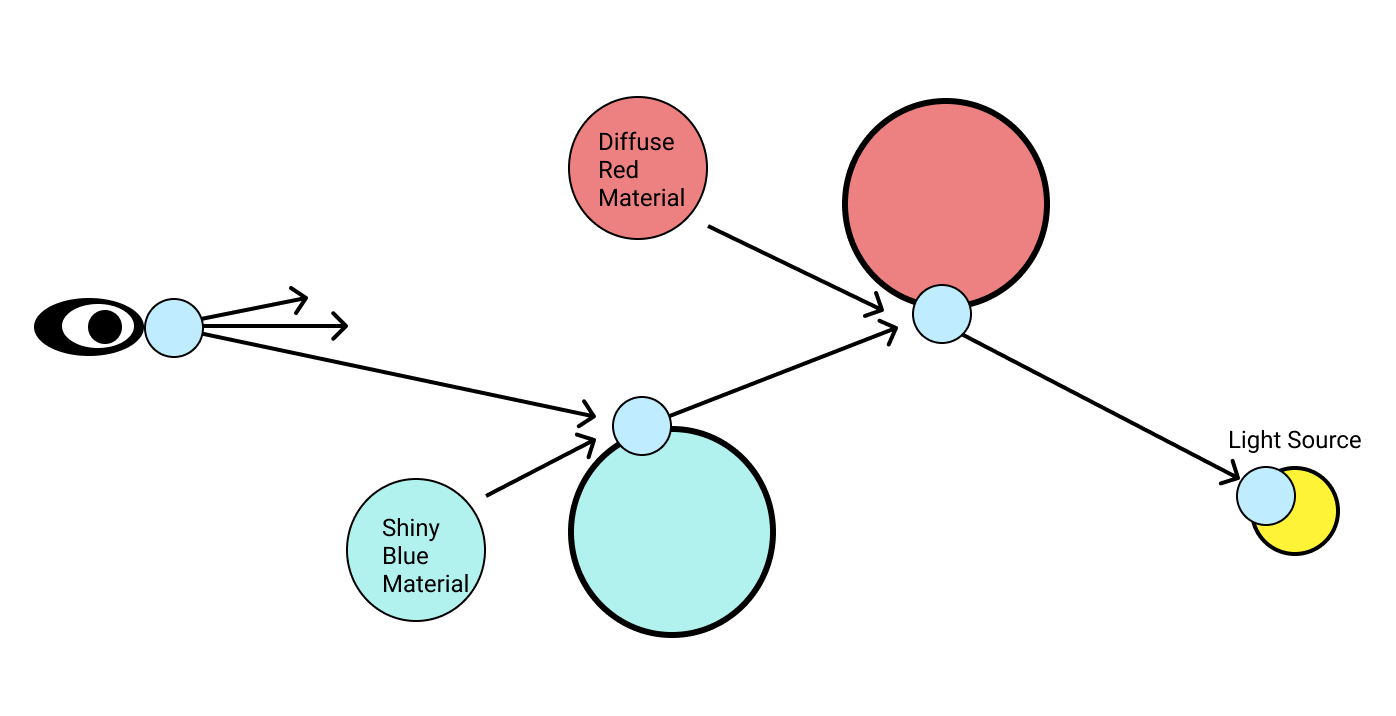

We can also fit additional metadata about our scene into the graph. For example, each object that a light ray hits will have a material associated with it.

In my model, these materials have color but also a "fuzziness" parameter that represents how reflective the material is. If the material is perfectly reflective, incoming light rays are reflected so that the angle of incedence is exactly equal to the angle of reflection. Otherwise there is a random jitter applied to the outgoing direction of the ray. The size of this jitter is controlled by the "fuzziness" parameter.

So the material parameters affect the final image color, as well as the direction of the outgoing ray. When the fuzziness of a material changes, we must recast all subsequent rays bouncing off of any objects which use that material. We can represent this dependency in our graph as follows:

In the above graph, if the fuzziness of a material changes, we will recast all subsequent rays.

Handling changing material parameters will be the focus of our render. The idea is that after an expensive render, an artist could tweak a few material parameters without having to redraw the entire screen.

But what about moving objects around? For this experiment, I decided not to implement this (fairly important) feature because I could not find a way to make it fit as nicely into the abstraction provided by Incremental. If I really wanted to do this, I'd basically just store all the rays inside a spatial acceleration structure like a octree. Then whenever a sphere's position changed, I'd query the set of rays intersecting it before and after it moved. I'd then recompute each of the nodes associated with these rays.

So anyways does this material editing approach actually work? The answer is somewhat.

Here's a gif of it in action (in real time)!

In the above gif, each material's color and fuzziness parameters are being changed one sphere at a time. Instead of doing a full render each time something changes, Incremental figures out which rays need to be recomputed. The image above looks grainy because I'm casting only about 10 rays per pixel (for reference, Shirley's code, which this is based off, does 100 rays per pixel). To see why I'm only taking 10 samples per pixel, let's look at some performance numbers:

| # Rays Cast (x129600) | Non incremental render time (s) | Inital incremental render time (s) | 50th percentile edit time (s) | 95th percentile edit time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1x | 0.864982 | 2.475083 | 0.010557 | 0.077140 |

| 2x | 1.559165 | 5.213949 | 0.015602 | 0.157500 |

| 5x | 4.088101 | 12.362720 | 0.032054 | 0.405897 |

| 10x | 7.763904 | 24.869927 | 0.088754 | 0.901066 |

| 20x | 14.815373 | 121.544599 | 0.840104 | 11.20906 |

| 30x | 19.766822 | 311.603921 | 1.917536 | 24.662991 |

Okay let's talk though this data quickly. The first four rows of the table tell a consistent story. The initial render has about a 3x to 4x overhead and editing a sphere's material results is significantly faster than a full redraw. All the numbers seem to scale linearly with the number of rays cast as expected.

But what about the rows after that? Runtime seems to explode in the incremental version. I was really surprised by this result. I don't have a definitive answer to this question but it did make me rethink the overhead that a library like Incremental brings to a program.

Overhead of Incremental

At first glance, accounting for the runtime overhead of Incremental seems like it would be pretty simple. Each node that is fired requires a little bookkeeping on the Incremental side. As far as I know this overhead is typically on the order of ~50-150ns per node on commodity hardware and should grow linearly. The operations we are wrapping are a lot slower than that, so this firing overhead should not be a problem.

While the bookkeeping overhead is minimal, there is a second kind of overhead introduced by using this library. This is the memory overhead. Incremental nodes are not super light weight by themselves. Each node weighs at least 216 bytes without counting the data it is pointing to. In our model, we have at least one node per bounce of light. In fact, there were 20,678,306 nodes in the row 5 computation. I didn't think about this memory overhead at first because I was concerned with runtime, not memory usage.

Of course, things are always more complex than they appear and I think it's possible that the runtime spike from above is caused by the memory overhead. As a disclaimer, I'm not an expert in profiling, so what say I could be very wrong.

As far as I understand, the memory that most programs have access to is not real memory, but an abstraction known as virtual memory. That virtual memory is divided into "pages" of about 4KB each (on my computer at least). These pages are typically stored in RAM. But when memory gets tight, the operating system uses a variety of tricks to create the illusion of having more RAM then it really does. These tricks include temporarily storing pages to disk, temporarily swapping entire programs onto disk, and compressing memory in RAM. The drawback of these tricks is a considerable overhead when accessing affected memory.

Let's assume that a page is always 4K bytes. In that case, about 20 nodes fit into one page. This means if we read all the program's memory sequentially we have to read from a different page every 20 nodes, which could incur some kind of extra cost. This is generally not too bad especially. However in the worst case, we could read all the memory in a different order such that we need to read from a different page every time! This could become very expensive if we are low on RAM because we could swap each page in and out of memory up to 20 times (also known as trashing)

The graph structure of incremental computations means that the nodes we read will likely not be right next to each other in memory, especially in larger graphs. This means that the overhead from swapping memory in and out of RAM could get quite large. This overhead is usually reflected by the number of page faults that occur. When I investigated, I saw an explosion in soft page faults between rows 4 and 5 of the table. Scaling to even larger numbers of rays (100x the number in row 1), I eventually saw an explosion of hard page faults as well.

What about the garbage collector you may ask? In my experiments there was a solid GC overhead but its overall percentage seemed to remain constant. I think that the mark step of the gc was likely dominated by same trashing problem, because it had to walk through the graph structure to check what was reachable.

While I'm not 100% percent convinced that the memory overhead is reponsible for all of the slowdown I saw, it was interesting to think about.

Take Aways

So was incremental a good fit for ray tracing? It was not the worst idea, but was absolutely not a great idea. For one, ray tracing is better done in high parallel environments, and Incremental is single threaded. A second reason is that ray tracing is a really well studied problem. There are tons of ways to accelerate it, none of which we used. There are even far faster incremental approaches that use of a lot of problem specific domain knowledge.

So why did I do this project? For me, it was a good way to play around with the limits of incremental computation. I think I learned a lot about structuring these graph computations and some of the specific pain points of the Incremental library. However I'm still pretty new to all of this so if you have any tips for me I'd love to hear from you!

Thanks to Robert Lord for teaching me everything I know about incremental computation, Ilia Demianenko for helping me profile my code and Gargi Sharma for teaching me OCaml.

Have questions / comments / corrections?

Get in touch: pstefek.dev@gmail.com