Using Bytecode Surgery to Create an Ouroboros

The code associated with this article can be found here.

Consider the following function in Python which sums up the first n numbers:

def sum(n, acc=0):

if n == 0:

return acc

else:

return sum(n - 1, acc + n)

So sum(1) returns 1, sum(2) returns 3 and sum(3) returns 6. What about sum(10000000)?

Most likely if you call sum(10000000) you will get the following error:

Maximum recursion depth exceeded

A quick google shows that we have exceeded a limit that Python has on how deep recursion can go. Why don't we just increase it to 10000001? Let's try it! Now what happens?

Most likely you will see a different error which looks like this:

Segmentation fault: 11

What happened here? It turns out that we ran out of memory. This is because every recursive call pushes a new stack frame, containing new variables and function information, onto Python's call stack.

But if you are incredibly observant or have taken a functional programming course, you might realize that the final result of this recursion is just the value returned by the base case. This value is then passed up a long chain back to the original call. It turns out in this case we don't need the chain. This observation is at the heart of so-called tail call optimization. The optimization eliminates unnecessary stack frames when calling functions from within functions. Most languages (even some js runtimes) implement tail call optimization, however Python's design committee has always been stubbornly against it.

Since I was looking for small projects to do during my first week at the Recurse Center, I decided to try to implement a basic version of tail call optimization in Python. Note this is not an original idea and I had already seen some clever hacks which used exceptions to break out of sub calls. I decided to try something different, although after presenting my implementation to the greater RC community I learned that another Recurser had given a fantastic talk which used the same idea back in 2015 (small world!)

Before I dive into the details let's look at the prototype in action:

sum.py is a file which contains the same sum calculation from the beginning of this post:

def sum(n, acc=0):

if n == 0:

return acc

else:

return sum(n - 1, acc + n)

print(sum(1000000))

If type python sum.py we will get an error.

Now let's try using my tool:

python optimize-tail-calls.py sum.py

This prints 500000500000 as expected.

Identifying Tail Recursive Functions Calls

The first thing I did was to come up with a way to identify which function calls can be optimized.

Let's say we have a function f which calls a function g inside of it (g could be a recursive call to f but doesn't have to be). If f just returns the value of g without modifying it, then we do not need to remember f existed in the first place (it does not have to stay on the call stack).

Let's see how we can translate that definition into something we can implement with Python.

A Byte Sized Definition

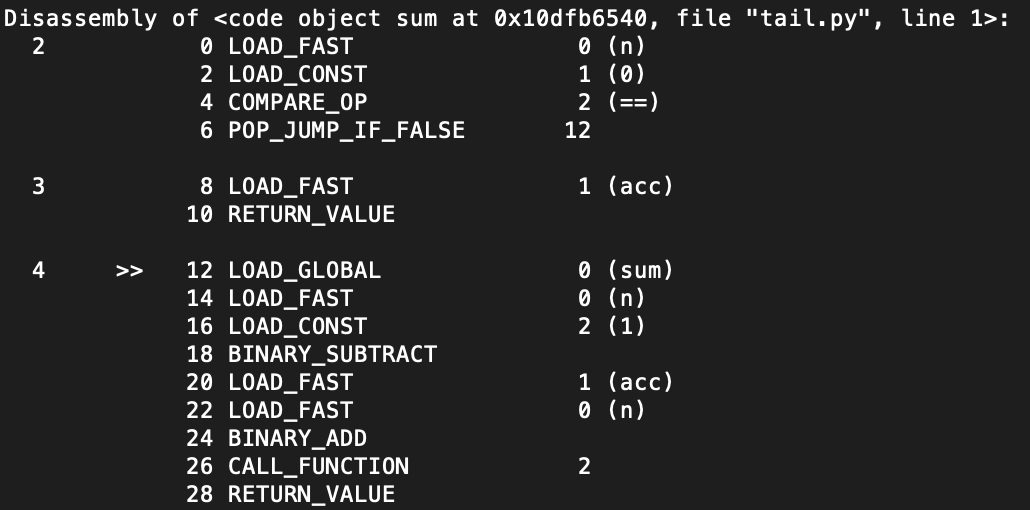

It turns out the Python VM does not evaluate python code directly but rather compiles it to an intermediate bytecode. Below is an example of the bytecode generated for our sum function from above,

This code may look familiar to anyone who has seen assembly language before. Basically it is a set of instructions which must be executed in roughly sequential order. As you can see here, the CALL_FUNCTION instruction comes right before the return statement. In theory, this gives us a pretty good heuristic to tell if a function call is a tail call. That is to say, a function call is tail call optimizable if it comes right before a return statement (or in some cases jumps to a return statement). Note this definition might not capture every case but does a pretty good job overall. It also should not have false positives.

✂️ Bytecode Surgery ✂️

Now that we know which calls are tail call optimizable, all we have to do is to remove the unnecessary stack frames right? Unfortunately this is where we hit our first big limitation of Python's VM. We do not have full access to the stack pointer like we do in some assembly languages. Therefore, we really don't have a lot of control over the call stack. This really limits our ability to optimize. Some Python tail call optimization implementations get around this by using the exception system to break out of the current call. I chose not to do this due to the complexity of exceptions.

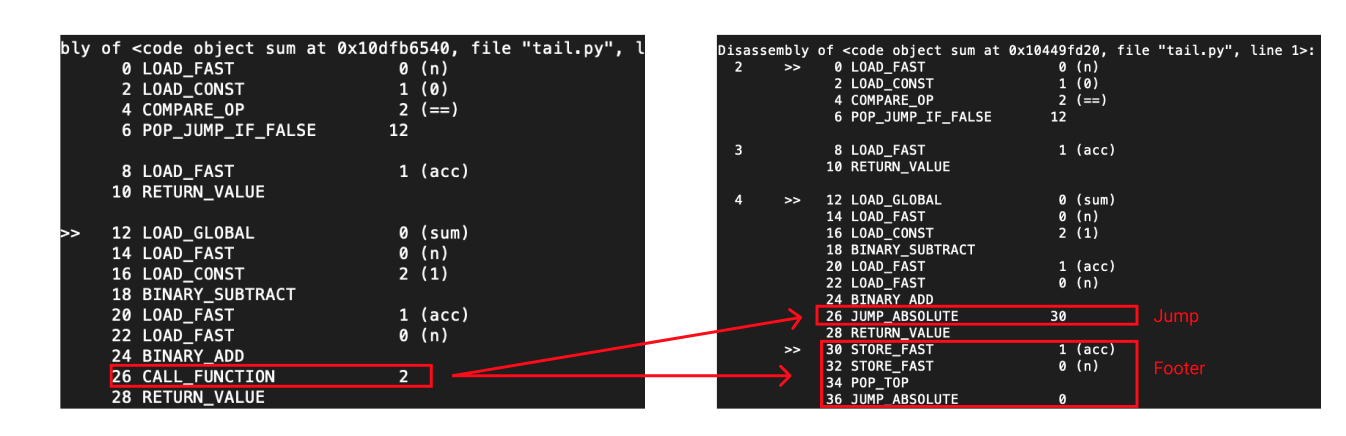

However if we focus our attention on tail recursive calls (where the tail call functions call the parent function) there is another way to hack around our problem. The simplified version is that we can replace the CALL_FUNCTION instruction with the JUMP_ABSOLUTE instruction, which we can use to take us back to the beginning of the current function.

Of course, reality is a little more complex. We actually have to insert more than one instruction to do things like store the function arguments into the proper variables and pop the initial function reference off the stack. To make things more complicated, Python will sometimes have jump statements elsewhere in the call. If we simply replace one instruction in the middle of the function with several instructions, all the indexes get messed up and things will break in subtle ways. The way I dealt with this problem was to replace CALL_FUNCTION with a jump which goes to the end of the function where we can append the rest of our instructions without having to worry about messing up other indexes. Of course this breaks for enormous functions but that's outside of the scope of this prototype.

More Complications

Unfortunately, there's one more major problem with our clean bytecode definition of a tail recursive function call. The problem is that there is no reliable way to tell from the bytecode which function is being called without actually running the bytecode. This means that in order to really know whether a tail call is tail recursive or not we need more information. I chose to use the AST (Abstract Syntax Tree) form of the code to figure this out.

To determine if a function call is tail recursive, I used another heuristic which consists of four criteria:

- the call is the sole direct child of the return statement

- the call calls the parent function

- the call and entire return statement must be on one line

- nothing unrelated to the return statement can be on the same line

This heuristic further narrows the number of calls we can mark as tail recursive. I think it can be improved but I chose it partially for simplicity of implementation. One other quirk about python's bytecode is that it gives us the line where each instruction is based but does not give us any more granular information. This is why I have the same line requirement.

We can now mark all the lines with tail recursive calls. Then when going through the bytecode, if we see a function call next to a return statement we can check if it is a tail recursive call or not based on the line number.

An Ouroboros

The Ouroboros is a snake which is eating its own tail. It symbolizes eternal cyclic renewal. In Python I consider this function to represent an Ouroboros,

def ouroboros():

return ouroboros()

Now that we can optimize tail recursive function calls, this function will run forever (read as until we send SIGINT), eating it's own stack in an endless cycle.

Further Places to Improve

I think with a little work the AST based heuristic could be complete (it would not miss any tail call optimizable functions).

When I started this project I was wondering about diving into the cpython VM code itself. I think it was neat that I didn't have to but I wonder if being able to make these tail call optimization decisions at runtime would be better. This would allow us to know which function was about to be called at runtime and we could decide whether or not to jump then. We would no longer need any AST based heuristics.

Of course if I had full VM access, I could also potentially allow jumping between functions without having to resort to exceptions which would really allow full tail call optimization. That might be an undertaking though.

Have questions / comments / corrections?

Get in touch: pstefek.dev@gmail.com